- Home

- Maureen McCarthy

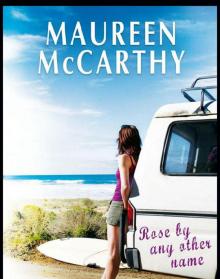

Rose by Any Other Name

Rose by Any Other Name Read online

Rose by any other name

MAUREEN

McCARTHY

Rose by any other name

First published in 2006

Copyright © Maureen McCarthy, 2006

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publisher. The Australian Copyright Act 1968 (the Act) allows a maximum of one chapter or ten per cent of this book, whichever is the greater, to be photocopied by any educational institution for its educational purposes provided that the educational institution (or body that administers it) has given a remuneration notice to Copyright Agency Limited (CAL) under the Act.

Allen & Unwin

83 Alexander St

Crows Nest NSW 2065

Australia

Phone: (61 2) 8425 0100

Fax: (61 2) 9906 2218

Email: [email protected]

Web: www.allenandunwin.com

National Library of Australia

Cataloguing-in-Publication entry:

McCarthy, Maureen, 1953- .

Rose by any other name.

ISBN 978 1 74114 909 8.

ISBN 1 74114 909 6.

I. Title.

A823.3

Cover and text design by Tabitha King

Cover title font is Marcelle by www.stereo-type.net

Set in 12/16 pt Baskerville by Midland Typesetters, Australia

Printed and bound in Australia by Griffin Press

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

For Patrice and Ramona who saw me through the bleak times. Thanks for all the love and laughter, the walks, the meals and the talk.

Thanks to Vince, too, for his love and support.

And special thanks to my son Patrick, a surfer, a musician and a Law student to boot, for sharing all you know about the great sixties and seventies bands and musicians and for introducing me to some of their present-day counterparts. Thanks for passing on your passion for the ocean, Pat. It gave me inspiration for this novel.

Warm thanks to Erica Wagner at Allen & Unwin for her belief in me when I had none. And many thanks to Eva Mills too, for her enthusiasm for the project, and for her meticulous attention to detail throughout the editing process.

Rose by any other name

I’m Rose. Rose Greta Patrice O’Neil. Rose. Not short for Rosemary, Rosa or Rosanne. Just Rose. The name is an embarrassment. I’m not beautiful or delicate or sweet smelling. I’m not even pretty.

So it’s Rose. My father told me that they took one look at me when I was born and decided on Rose because I was pink and crunched up, and I exuded an air of superiority. Well okay, thanks, Dad. But I’ve seen the photos and I don’t look anywhere near as superior as my three older sisters. Hilda. Cynthia. Dorothy. All of them were stunners and they still are. He said it to make me feel better. He is a barrister. They know how to use words.

I never expected love to come when it did. Nor the way it came. Nor the complete mess it made of my life. I wasn’t hanging out for it either, like some people. My life was fine. Great family. Excellent academic results. I got on with people in my own way and I had a best friend to laugh with and bitch with.

But love found me. It came straight at me like a howling wind. Knocked me to the ground, made me blind, chucked me in the air. And when I crashed, well . . . I thought everything was over.

But things are never over even when they’re over. I learned that. They change. You think they won’t but they do. Everything changes all the time. That trip I took with my mother was the beginning of things changing for me . . .

Road Trip

I can’t believe I’m doing this. Can’t believe she talked me into it. Had me feeling awkward, obliged and compliant all within about a minute. I should have held firm. Should have said no.

I glance at myself in the rear-vision mirror, so pale and . . . mean-looking with my chopped-off hair and blunt, freckled nose. Mouth like a piece of string. Nineteen years old and I’m sitting stiff as a plank behind the steering wheel, waiting to start the engine. For God’s sake ease up! Chill out. When exactly did I get like this? I poke my head out the window and look up at the summer sky, so deep and clear and blue, as innocent as a kid’s drawing. Nothing can be that simple, I want to yell. Don’t lie to me!

‘Ready then?’ I ask without turning around.

‘Yep. I’m ready.’

I pull down the seatbelt, slip the buckle in and settle it tight across my chest. Concentrate on what you’re doing Rose, I tell myself. Just concentrate on what you’re doing and everything will work out. Turn the key. Okay. It starts first go. So it should. It’s just been serviced. The lighted dashboard tells me I have plenty of petrol. Oil is fine too. The blinkers are working perfectly. Even the temperature gauge is smiling back at me with the black needle hovering slap bang in the green band. Sweet. This engine blew once, right in the middle of Punt Road. I lifted up the bonnet without thinking and . . . whoa! The cap blew off. Boiling water everywhere. Black smoke. Stinking fumes. The works. Lucky I didn’t get badly burned. No one stopped. They just scooted past like I was a terrorist fussing over a dud bomb. Since then, I get scared if that needle goes anywhere near the red.

My bag is in the back. Wetsuit. Surfboard tied on the roof. What a laugh. I haven’t even seen the ocean inside a year much less considered surfing! (I do dream about it though.) I’ve got the old rubber mattress. Pillow. Sleeping-bag. There is some satisfaction in knowing that I’m ready for anything. I push the indicator down and pull away from the kerb. Clutch down and I slam it into second gear. We’re away.

‘Rose, I think I might have forgotten my credit card.’

I step on the brake and stare straight ahead, hands gripping the wheel. You’ve got to be joking!

‘Well?’ I say, shitty as hell and not bothering to hide it. ‘Have you or haven’t you?’ I turn and see that she is looking at me instead of checking in her bag.

‘Don’t snap, darling,’ she says, before bending to search in her big, bright-orange, ridiculous straw bag. ‘It’s not that important.’

‘Sorry,’ I mutter, thinking that it really is every bit that important. The only way I agreed to her coming was when she said she’d stay in a motel if I decide to sleep a night in the van (which I’ve already decided to do although I haven’t told her). How will she pay for it without her card?

‘But you will need it.’

‘I know.’

‘Any idea where it might be?’ I ask through gritted teeth.

‘Yep.’ She slides open the van door. ‘I’m pretty sure it’s on the kitchen table. Won’t be a jiffy.’ She hesitates a moment, smiles and stretches one hand out, as though she’s about to run her hand across the top of my chopped-off, inch-long totally in-your-face hair. Thankfully she thinks better of it and pulls away.

‘I can’t get used to it!’ she says lightly, pretending that she’s open to liking it when she does. I shrug sourly, as though her problem with my hair isn’t any concern of mine. As though I’m completely at home with my new, weird, aggro image when in fact I’m totally freaked out by it and I can’t wait for my hair to grow back.

‘Don’t go without me!’ she calls gaily.

‘I won’t.’

I watch my mother jump out and run back towards our huge double-fronted family home on Alfred Crescent in North Fitzroy. She is dressed in well-cut red linen pants, a loose white cotton blouse with a frill around the wide neck, heeled sandals and those long beaded aqua earrings that I like and wish I’d accepted when she offered them to me some months ago. Her dyed red hair is up in a lo

ose bun and she looks good for her age. Fifty-two years old now. My sisters threw her a party last month and I didn’t even pretend I had something else on. Parties and me don’t connect these days and I think everyone understands that now.

I reverse the van into a park just outside our gate and watch as she pushes open the wisteria-covered wrought-iron gate and makes her way up the pathway to the front door. I’m gripped with a sudden mad impulse to run after her before she disappears inside. To grab her and hug her tight, tell I love her, just in case I never see her again. But the moment passes, thankfully. It’s gone . . . almost before it registers. Anyway, as though that’s going to happen! As though she’s going to disappear into thin air. God, Rose, get a grip.

The rambling garden around our family home is wonderful at this time of the year. It’s filled with leafy trees and bright, chaotic climbing plants: clematis, sweet pea and roses that cover the fence and creep up along the edge of the house steps. There are ferns and little pockets of bright summer flowers too. It’s all so lovely that it could make your throat close up if you let it, which I don’t.

I got this van last summer. Only two and a half thousand bucks. I’d saved most of the money over the previous year. There was a year or two left on the tyres, six months rego and the engine – according to the RACV man who checked it out for me – was in good shape. I’m not sorry. When the shit hit the fan I still had the van, which was something.

I turn off the engine and look at my watch. Five minutes already. The credit card is obviously not on the table. Then again, knowing my mother, she’s probably in there pulling together half a dozen other things she’s forgotten or thinks she needs. Or she might be making a last phone call, or taking one, or . . .

It’s eight thirty on a weekday morning. We’re going to be caught in peak hour traffic on our way out of the city and there is no one to blame but myself. I was meant to be here over an hour ago to pick her up. I slept in later than I’d planned and when I did get up I messed around. Went to ring her at least three times and tell her that I’d changed my mind about her coming with me. After all, she has her own car. A top-model, stylish Saab with airconditioning, bucket seats, automatic gears and a great sound system. Dad bought it for her when she turned fifty. Driving the Saab the shorter way through Colac and Camperdown she could be in Port Fairy inside four hours. She’d be able to book into a motel before nightfall and be rested when she goes to see Grandma Greta.

Whereas I’m going the long way, around the steep and winding coastal road through the Great Otway National Park, where it’s sixty kilometres an hour for hours. I told her this. I was frank and uncompromising about my plans. I’m going to stop when I feel like it. I’m going to walk on the beach. Look at the cliffs. Chill out. Put my feet in the water. Have a swim if I can bring myself to. I don’t care if Grandma does die before I get there. I mean it. She’s eighty-six. According to my sister Dorothy (who is already down there), she wants to die. Where is the tragedy if someone of eighty-six dies when she wants to? I can’t see the point of fond farewells and last goodbyes.

But when I got here this morning my mother was waiting for me on the front verandah. Case at her feet and that wide straw sunhat on her head, looking so keen. What could I say? I just gulped, got out, walked over and said, ‘Hi Mum. You ready?’

‘I’ve been ready for ages!’ she said, and kissed me on both cheeks.

Ah! Here she is and yes, she’s carrying a brown paper bag as well as, hopefully, her credit card.

‘Sorry love,’ she puffs as she climbs in.

‘You get it?’

‘Yep.’ She grins at me. ‘And the lunch I so carefully packed for us.’

‘Where was that?’

‘On the table, too.’ She laughs and I can tell she wants me to join in. To indulge her zany forgetfulness with at least a smile. Oh, there goes Mum again. Dithering along, messing up the practicalities . . . But I turn away and start the engine again. I pull out and nose my way into the St Georges Road traffic without giving even a hint of a smile. I actually like attention to detail. Taking proper care of the small bits and pieces of whatever is going on is what life is about, as far as I’m concerned. Why should I agree that leaving a specially prepared lunch to go to waste is something to laugh about?

‘So what exactly did Dorothy tell you?’ Mum opens up the conversation in this intimate aren’t-we-going-to-have-fun-together kind of way that immediately gets my back up. ‘About Gran, I mean.’

We are heading around the zoo now and the traffic is diabolical. Everyone is coming into the city to work and all the roads and intersections are congested. I keep myself from losing it by clinging to the thought that we’re going the other way. Once we’re over the West Gate Bridge it will be okay. Just got to get out of this.

‘Dorothy said Gran is fading fast and wants to see me,’ I say sharply.

‘But why you?’ Mum asks, then quickly tries to correct the impression that her nose is out of joint. ‘Not that it’s strange to want to see you, but why you particularly? Why not . . . everyone else?’ she finishes lamely. I don’t take offence because I don’t know the answer. I’m intrigued too. Why me? I have never had a particularly special relationship with my father’s mother Greta. Hilda, the eldest sister, was always her favourite and the other two also seemed to shine more in her eyes than I did. But I am fond of her in a way. I guess we all are. She is a wiry old bird, bossy as hell and full of punch. Or was. She’s on her last legs now. Demanded to be allowed to go home from hospital to die in her bed. Her words, not mine. So I guess she figures her time is up.

My grandfather was a fisherman who drowned at sea when Dad was just a baby. Gran has lived in the same little cottage in Port Fairy all her life. It’s where my father, who is an only child, grew up. Four small rooms with a dark hallway leading down to the kitchen. Never renovated but on a huge block. We used to spend our summers there when we were little.

As soon as my sister Dorothy heard that Gran wanted to go home to die, and that there was no one around to stay in the house with her, she managed to negotiate some time off from her glamorous television job and went straight there to look after her. Pretty heroic, considering how difficult Gran can be. Then again, the grand gesture is what Dorothy’s good at. Theatrics is her game.

Dorothy is the sister nearest to me. Twenty-three years old and a bit of a flake compared to the rest of us. Not dumb. She consistently came top in just about every subject at university, and she was studying for her Masters in Classics until last year. I don’t know anyone else who speaks fluent Latin and Greek, or who knows everything there is to know about everything that happened before 500 CE. It’s just that Dorothy has real trouble with most of what’s happened since, if you get my drift.

But that’s all changing too. Dot’s life did a total flip last year when she was plucked off the street – literally – to act in a television soap opera. All of my three sisters are very good-looking but Dot is quite simply gorgeous. I’m not kidding. She’s got these huge, deep lavender eyes with lashes like long Japanese paintbrushes. Her hair is thick and dark and curly. She has fairer skin than the rest of us and the loveliest mouth, like a rosebud. (She is the one that should have been called Rose!) Even before she was on telly people used to gape at her in the street.

‘Gran wants to give you something?’ Mum murmurs.

‘Yeah.’

‘Any idea what?’

‘Dot didn’t say,’ I reply shortly.

‘Maybe she’s going to leave you all her money.’ Mum smiles.

‘Maybe,’ I say dryly. We both know that there is no money. Gran has lived on the old-age pension for the last twenty years and the cottage is already in Dad’s name.

‘Maybe you’ll get the Collection,’ Mum says lightly, after a careful little pause. This gives me a nasty jolt. Shit! I never thought of that.

In my consternation I forget to take my foot off the clutch slowly enough and the van lurches forward, almost collecting a l

ittle red Mazda pushing in to the main stream from a side road. I wave in the driver irritably. Damn it. Mum’s probably right! The Collection. Yeah, that’ll be it. So I’m on a six-hour drive for something I seriously don’t want!

‘It’s very precious to Gran,’ Mum adds cajolingly, like this might make me change my mind. Like I might suddenly start loving a heap of cheap old rubbish because some crazy biddy in her eighties has held it dear for fifty years.

‘You might end up really . . . valuing it.’ Mum’s voice peters out when I turn and give her my best withering look, daring her to continue. Yeah right, Mum!

‘Oh well,’ she sighs, ‘stranger things have happened.’

Naturally, I’ve been hoping for something nice, an antique bracelet maybe or a ring that Gran had been secretly hoarding all these years for her youngest grandchild. But no . . . I try to shrug off this secret hope. Better to expect the worst.

‘Do you know this, like, for sure?’ I ask after a few moments have elapsed. ‘Did Dot give you a hint?’ Mum shakes her head so vigorously that I reckon she has a fair idea but doesn’t want to hit me with the full, 100 per cent horrible truth in one hit. Mum is the family diplomat, very good at breaking bad news.

‘I’m only guessing,’ she says.

‘Well I don’t want it,’ I mutter sourly.

‘But there is no way you could throw it away,’ she says insistently. ‘I mean if she leaves it to you, you can’t just . . . dump it.’

I don’t reply because she’s right. No way could you toss the Collection in the bin. It is so much part of Gran and that little house that it would be an extremely sacrilegious and violent act. People don’t mess with Gran or they cop it. I’m not normally superstitious, but if I threw the Collection away I know I’d live the rest of my life in fear that she’d get back at me some way – even after she was dead.

The Collection consists of about two dozen cheap, kitschy porcelain cats in a variety of inane postures, with mawkish expressions, insipid colours and broken-off tails with patchy paint. Think the worst and you’ll be right on the mark. Gran has always displayed them in her best room on top of the crystal cabinet. A cat lover all her life, each one commemorates the passing of one of her real cats who were all named after someone Gran admired, like Nelson Mandela or Bert Newton. So they all have personalities and names and histories . . . right back to the 1940s. Gran is not senile, or crazy in any other aspect of her life, but she dusts and rearranges these cats daily . . . and talks to them. If she manages to get you in the best room (which, incidentally, is hardly ever used for anything else) for a guided viewing of the Collection, you won’t get out again inside two hours.

Careful What You Wish For

Careful What You Wish For When You Wish upon a Rat

When You Wish upon a Rat The Convent

The Convent Queen Kat, Carmel and St Jude Get a Life

Queen Kat, Carmel and St Jude Get a Life Rose by Any Other Name

Rose by Any Other Name