- Home

- Maureen McCarthy

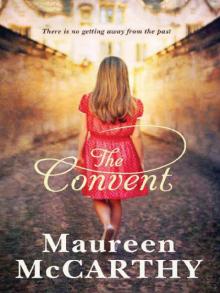

The Convent

The Convent Read online

Also by Maureen McCarthy

Rose by any other name

Somebody’s Crying

Queen Kat, Carmel and St Jude Get a Life

Careful What You Wish For

Flash Jack

Chain of Hearts

When you wake and find me gone

Cross my heart

Ganglands

In Between series

Maureen

McCARTHY

This project has been assisted by the Australian Government through the Australia Council, its arts funding and advisory body.

First published in 2012

Copyright © Maureen McCarthy, 2012

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publisher. The Australian Copyright Act 1968 (the Act) allows a maximum of one chapter or ten per cent of this book, whichever is the greater, to be photocopied by any educational institution for its educational purposes provided that the educational institution (or body that administers it) has given a remuneration notice to Copyright Agency Limited (CAL) under the Act.

Allen & Unwin

83 Alexander Street

Crows Nest NSW 2065

Australia

Phone (61 2) 8425 0100

Fax (61 2) 9906 2218

Email [email protected]

Web www.allenandunwin.com

A Cataloguing-in-Publication entry is available from the National

Library of Australia www.trove.nla.gov.au

ISBN 9 781 74237 504 5

Cover design: Kirby Armstrong

Cover photo: © Mark Owen/Trevillion Images

Printed and bound in Australia by Griffin Press

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

The Convent is a work of the imagination. Apart from some known aspects of my mother’s early life no resemblance to real people is intended nor should be inferred.

As far as possible I have tried to make the personal dates of my characters tally with the historical chronology of the Abbotsford Convent, but I have taken some liberties. For example, Peach’s story – the ‘now’ of the novel – takes place in 1999. At that time the fight to save the Abbotsford Convent from development was only just beginning; there were no painters’ or writers’ studios. The Convent as it appears when Peach works there is very much how it is today – a vibrant, bustling, artistic community with cafes and galleries and bars. Any mistakes made regarding convent conventions, in dress, ceremonies, speech or anything else are entirely my own.

Maureen McCarthy, 2012

For Sadie, the grandmother I never knew

You may find in that far-off land to which you go, sorrows which

may often fill your Chalice to the brim. Yet I say to you, Go!

my dear daughters, go with great courage where God calls you!

St Mary Euphrasia Pelletier

Foundress of the Congregation of the Good Shepherd

Contents

Peach

Sadie 1915

Ellen 1926

Cecilia 1964

Peach

Cecilia

Peach

Cecilia 1962

Peach

Cecilia

Peach

Cecilia

Peach

Cecilia 1968

Peach

Cecilia 1972

Peach

Cecilia

Peach

Cecilia

Peach

Cecilia 1970

Peach

Ellen

Cecilia 1972

Peach

Sadie 1916

Peach

Cecilia 1968

Peach

Cecilia 1973

Peach

Cecilia 1979

Peach

AUTHOR’S NOTE

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Peach

My sister and I often rode past the convent that summer.

I’d been trying to get her to do some exercise every day – apart from the three hundred daily trips she took back and forth from the chair to the fridge – and bike riding was the one thing she didn’t mind. Most evenings I was able to cajole her out when it was still light enough to see but dark enough for her not to feel too exposed.

We’d head down the backstreets to the river, and at Dights Falls we’d turn right onto the bike trail and follow the river towards the city, zooming under the Johnston Street bridge and through the Collingwood Children’s Farm. It was a nice easy ride, a winding track with little hills and flats and corners, not too hard on the muscles and plenty to look at on either side.

At that time of day there usually weren’t too many people about to stare at the large olive-skinned girl with the wild black mane, cycling in stately fashion behind her slim, fair-haired sister. The brown river was on our left; on our right was a cliff face dotted with natives, the odd palm and clumps of peppercorn trees, or concrete walls covered in wild graffiti. When we came to the farm there were horses and goats and cows, even bee boxes and a few wonderful old oaks. Once we were through to the open space of the river flat we could look up to our right at the massive grey building that was known locally simply as ‘the convent’.

We got into the habit of stopping there so Stella could catch her breath. She liked to lean against the fence and wax on about the spires and turrets visible through the trees, and how interesting it would be to go back in time and see what really went on there.

It was all a bit of a ruse, I think, to stop me getting her back on the bike too quickly, but I liked looking at the convent too, especially towards evening when some of the lights were blazing, and the beat from a band playing outside the cafe and the smell of cooking would waft down to the bike track.

We knew it had been set up by French nuns back in the 1860s and from then until the early seventies it had operated as an industrial laundry, a farm, an orphanage and a school, as well as a home for destitute women and girls in trouble. Once the nuns left and the place closed down there was a long fight to save it from the housing developers.

But all that was long over by the time Dad and Mum shifted to Collingwood to be nearer their work in the city. The place had stood empty for years. Now the old dormitories and refectories and parlours were in the process of being renovated and let out to health practitioners and theatre companies, artists and writers.

But when Stella and I stood musing in the middle of our bike ride, it was mostly the past we were trying to conjure up.

Why would anyone choose to become a nun? Who were the orphans? What about the bad girls who’d been locked up there? What crimes had they committed?

We were not from a religious family, so the lives of the women and girls who’d lived there were enticingly remote.

I liked the way the building seemed to change mood. Against a pale blue sky or a pink-and-gold sunset it looked full of magic, as pretty as a castle in a young girl’s fantasy. But when the sky was low and grey with cloud, the buildings took on the menacing undertones of a jail.

Sometimes we’d wander through the gate and up along the gravel path through the garden that had been laid out in the French style. The renovations were only partly completed, and large parts of it still weren’t open to the public. But it was easy enough to peer into the big industrial spaces where the girls had worked the laundry, eaten meals and gone to church.

The gate through which the trucks had driven every day to collect the laundry from the St Heliers Street entrance was still there, battered and rusty. You could see where they’d stored the coal and wood, and the huge

iron boiler that had heated water for the whole place.

One evening we snuck past the developer’s wire fence, through a door and upstairs to wander through the Magdalen dormitories. The few rows of abandoned iron beds, the sinks along one wall, the battered cupboards and dusty shower cubicles made the huge rooms eerie, as though everyone had left in a hurry. Apart from thin shafts of late-afternoon light coming through the cracks in the boarded-up windows it was more or less dark inside.

It got a whole lot more eerie when Stella swore she could smell the girls who’d slept there, that she could feel their spirits, too, hovering with the dust mites in the corners of the empty rooms. I told her she was crazy, that the place had been closed for almost thirty years, and yet … I believed her. Stella couldn’t tell a lie if she tried.

I had no idea then of my own connection to the convent. I’d only just turned nineteen and, to tell you the truth, I didn’t want to know. There was enough on my plate already. Mum and Dad were overseas. I had my studies, a summer job, a best friend in the middle of a huge drama of her own making, and a sister I was meant to be caring for, who, for reasons of her own, seemed intent on doubling her size.

And there was Luke, too, of course. Luke ‘the Fluke’ Robinson, my former boyfriend with the smoky grey eyes, who had been saved from drowning when he was three years old by his mum who couldn’t swim until she found out she had to.

He used to tell me that there was no getting away from the past; that wanting to know your own history is as basic as the need to take your shoes off at the beach. That first touch of icy water, the million sand granules squishing between your toes, the vast expanse of sky above, and you know … you just know you have a right to be there.

Well, he was right in a way. The past does come after you whether you like it or not. It blusters in like a noisy drunk off the street, tapping you on the shoulder, demanding to tell his story. You resist at first because you have better things to think about, then you make an excuse to slip away, and when that doesn’t work you listen out of politeness, impatient for the end because the story doesn’t make much sense. There is none of this followed by that, the way a story is meant to go. People and events drift in and out as they please, running together like drops of water on a grimy windscreen, reforming, breaking apart, and flying off in different directions.

But you get hooked anyway, and when the story is over you see it makes its own kind of sense.

It is then you understand that all you’ve ever known about yourself and your particular place in the world has shifted position. You’re left wondering how you’re meant to deal with it.

But you do. That’s the good part. You do.

Sadie, Ellen, Cecilia and now … me.

Sadie 1915

It began at daybreak with three hard knocks on the door, and light sneaking like a thief through the holes in the blind. Sadie woke on the third knock and reached for her dressing-gown. She was two weeks behind with her rent and the old skinflint who owned most of the street made it his business to call early if someone needed a warning.

Not to worry. There was three pounds ten in the pocket of her gown, and a little more in the drawer near her bed. With a bit of luck she’d have enough to pay the milkman as well. She could hear the faint clip-clop of his horse in a nearby street. Whoa there, girl …

She smiled through a thick head and dry mouth and felt for the extra money in the side drawer. Bill the milko had cut her plenty of slack over the years; she’d see him right.

By the time she had opened the door of her tiny Carlton terrace her feet were freezing. She was met with thick white fog and two people, neither of them the landlord. A heavy, red-faced woman dressed in some kind of grey uniform was closest. She had short, steel-grey hair and narrow eyes, hard as splinters, and she was carrying a blanket over one arm. Next to her stood a fresh-faced copper, all done out in brass buttons, a cap and shiny black boots. He had a long baton in a holster by his side.

Sadie held firm. It didn’t do for a woman living alone to show fear. Her first thought was for the boy, William, living with his father now, cutting stone in some godforsaken place up near Echuca. She clutched tightly at her dressing-gown and snarled a quiet prayer to the God she had no time for these days. Let the kid live.

It was only then that she saw the third person. Lurking behind the other two, his hat pulled down over his eyes, pretending he wasn’t there, was Frank! What the hell was that sanctimonious little bastard doing knocking on her door at six in the morning? Sadie caught his eye and he edged further back. She had to stifle the jeer that rose like bile from her guts. Under the thumb of a hypochondriac wife for twenty years and run off his feet with two carping sisters, it was a wonder he’d managed to get himself off the chain for the early-morning outing.

‘Yes?’ Sadie said.

The copper shoved some kind of document under her nose.

Sadie waved it away. ‘I can see you’re a copper,’ she said. ‘What you here for?’ Reading wasn’t her strong point, but that wasn’t for him to know. Let that slimy little bastard Frank tell them if he must.

The copper didn’t say anything at all, and neither did the other two, but they looked at each other, shifty and sly-eyed, as if they were unsure how to proceed seeing as she’d refused their bit of paper.

She folded her arms and waited, apprehensive but righteous. It was freezing, she had over a month of rent in her pocket and this was her front door.

‘You should read it,’ the copper said uncertainly, trying to sound as if he knew what was what, when everything about his silly young face told her he was out of his depth.

‘Why?’

‘It’s the law.’

‘Is that a fact?’

‘Yes.’

‘What law says I’ve got to read it?’

‘Otherwise you won’t know what we’re here for.’

‘Can’t you tell me, Officer?’ she mocked. He would have joined the police as a face-saver when all his mates were volunteering. Not that she blamed him, of course. Why get your head blown off if you didn’t have to? Even so she wanted to jeer, Decided to keep your skin on, did ya, shirker?

The other two were looking at her with curled lips and it angered her. Maybe her dressing-gown was grubby and she had no slippers, but it was six o’clock in the morning and … Sadie pushed her shoulders back, pulled her belt tighter and reminded herself that she’d never pretended to be anything she wasn’t. She fed her little girl well, kept her clean and kept a decent roof over their heads. Sometimes only just … but still. What right did they have to look down their noses?

‘And what brings you here, Frank?’ She was already imagining telling Dottie about this later. Too gutless to come on his own! He brings the jacks and some fat bitch from the government to my door at daybreak and expects me to stand there trying to guess what he’s about.

The words were spilling around in her head, but her mouth stayed tight. Dot was going to love this. Snatch a laugh or two when you could else you’d go barmy was her theory, and as far as Sadie was concerned it wasn’t a bad one. Stories that stuck it to the jacks sent them both off like tops.

Frank was behind this, whatever it was. If the copper hadn’t been there she would have given him a piece of her mind, told him to keep the few measly quid he gave her every month if that meant she never had to look at him again.

He still couldn’t meet her eye.

‘You are Mrs Sadie Reynolds?’ the copper asked stiffly, as if he had the baton up his rear end.

‘Yes.’

‘Where is your husband?’

‘That’s my business.’

‘Where is your husband, Mrs Reynolds?’

Sadie knew she’d better start toeing the line or there’d be more trouble. ‘If you must know, he is up north, working.’

‘You keep in contact with him?’

‘Yes,’ she spat. ‘Of course I do.’

It was a lie but so what? Joe turned up for a feed every now an

d again, and for whatever else took his fancy. Last time it had been the boy, and they’d fought cat and dog over that one but … what use dwelling on it? She didn’t have the money to feed a growing boy and they both knew it. Joe would let her starve without blinking an eye, but that shouldn’t mean the kid had to. To all intents and purposes her husband was gone, and he’d taken their son with him.

‘Well, Mrs Reynolds, we don’t want any trouble now,’ the copper said uncomfortably.

‘Nor do I.’

‘So where is Ellen?’

‘What?’ A shaft of ice went straight to her guts, and her bowels began to churn.

‘Ellen,’ the young man said again, triumphant now he could see her fear. He looked down at his bit of paper. ‘Ellen McIntosh Reynolds. Three years old. Where is she?’

‘Where do you think?’ Sadie said loudly, trying to still the panic, but her voice sounded hollow as if she was in some kind of cave. ‘In her bed asleep.’

The three of them looked at her impassively. She almost told them to go and take a look for themselves if they didn’t believe her, except that would be inviting them in and that was the last thing she wanted.

‘May we see her please?’

‘No.’

‘Mr McIntosh wants to see the child, Mrs Reynolds.’

‘Well, he can’t!’

‘He is the child’s father, Mrs Reynolds.’

‘So?’ For the millionth time she cursed her own stupidity. In a crazy fit of honesty she’d put his name on the birth certificate. The child had her husband Joe’s surname, of course – that was the law – but seeing as she’d hardly seen Joe over these last few years she decided to stick Frank’s surname in the middle. The poor little mite needs to know who her real dad is. Oh why had she done that? It gave him ideas above his station, made him think he had rights far and beyond what was the case.

She turned to Frank. ‘What do you mean bringing people here?’ she hissed, trying frantically to grab the doorknob without taking her eyes from his face. Her father had been a tough Scot, and he’d taught her that the chances of winning are always better if you stand your ground. But the door had swung wide open behind her and she was unable to catch the knob.

Careful What You Wish For

Careful What You Wish For When You Wish upon a Rat

When You Wish upon a Rat The Convent

The Convent Queen Kat, Carmel and St Jude Get a Life

Queen Kat, Carmel and St Jude Get a Life Rose by Any Other Name

Rose by Any Other Name