- Home

- Maureen McCarthy

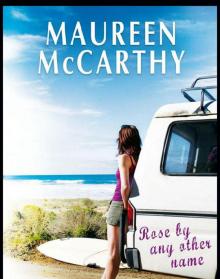

Rose by Any Other Name Page 2

Rose by Any Other Name Read online

Page 2

‘What will you do with it?’ Mum is all innocence. ‘I mean, if she gives it to you?’

‘Leave the country. Slit my wrists.’

‘Now Rose!’ Mum laughs uneasily. She’s not sure if I’m joking, and neither am I.

At last the light turns green and we inch forward a few feet towards the Flemington Road intersection. I hold my breath and step on the accelerator. Don’t let the lights turn red again so soon. They hold and we’re across.

‘What is Dot actually doing down there?’ I think of flannels and bed pans and Dorothy’s slight frame trying to lift Gran’s bulky body. It’s hard to imagine my dippy, hothouse flower of a sister in any kind of practical role at all, much less that of nurse.

‘Not sure,’ Mum says.

‘Bath her maybe?’

‘Goodness!’ Mum is shocked at the thought. ‘I can’t imagine it.’

‘Feed her?’

‘Maybe.’ Mum begins to chew her thumb, a sign that she’s thinking hard. ‘Dot said she just wanted to be there.’

‘Oh well,’ I say hastily. ‘Good on her.’

I guess we’re both flummoxed. Dot doesn’t usually do practical life very well.

‘Maybe the tablecloth is in doubt?’ I suggest. I mean it as a joke but Mum nods seriously.

‘That could be it.’

Even though Gran’s cottage is packed to the rafters with all kinds of junk, there are only three things that any one wants. They are all wedding presents given to my grandparents in 1945: the crystal cabinet in the front room which is all polished cut glass and deep shiny wood; an almost complete set of Royal Doulton 1920s yellowing crockery with little green flowers around the edges; and this incredibly lovely embroidered linen tablecloth, covered in birds and flowers from Chinese mythology. My three older sisters have had these things assigned for years. Hilda gets the crockery – although why she wants it so badly is a mystery. She and her husband could afford a dozen sets twice as good. Cynthia is desperate for the cabinet, for her surgical instruments. And Dorothy believes the tablecloth is rightfully hers because the embroidered Chinese bird motif is her sign. As the fourth sister it’s always been understood that I miss out, but I honestly don’t mind. I’ll probably end up doing better than all of them anyway, as each of my sisters feels so guilty about me not getting one of the Big Three that they’re always promising to make it up to me in ‘other ways’ when the time comes. Over the years I’ve secretly figured that I should be able to play this number for all it’s worth when the time comes – and get something out of them that I really want!

For all I know, Gran wanting to give me something may have thrown a serious spanner into their settled arrangement. General gnashing of teeth and forming of secret alliances might already have begun. Then again, if they know I’ve been given the Collection, the three of them will be lying around weak with relief that they missed out, which makes me doubly pissed off.

‘The council provides a nurse,’ Mum says after a while. ‘Dot is probably just keeping Gran company. Reading to her. Giving her tablets, making tea. That kind of thing.’

‘Right.’

‘It should be Cynthia,’ Mum muses. ‘After all, she’s the doctor.’

‘You have got to be kidding!’ I splutter incredulously.

‘Yes of course,’ Mum mumbles quickly, ‘only joking.’

They are only fifteen months apart but Cynthia and Dorothy are chalk and cheese. Dot is all airy-fairy and convinced that the world would be a better place if everyone spoke Latin and rode their bicycles to work. Cynthia is efficiency plus, or thinks she is. She’s twenty-four and will soon be a qualified doctor, which fills the rest of us with total pity for any patient she’ll ever come across. I’m not kidding. She’s the doctor who, if you went in with the flu, would tell you to go home and start making your will because you’ve most likely got a brain tumour. Once Mum had tinea between her toes and Cynthia diagnosed her with some totally weird African skin disease. She didn’t hold back with the bad news, either. By the time Mum got to her own doctor – who had never heard of the African disease – Cynthia had her believing that she would be covered from head to foot with pus-filled blisters which might or might not respond to some new cortisone ointment that would have to be flown in from America.

Dad reckons Cynthia will settle down once she gets to the hospitals for some hands-on experience with real people. But the rest of us seriously doubt anyone under Cynthia’s care will even survive. Just how many real people will have to die or be sent absolutely crazy before she settles down is what we want to know!

So we’ve just come off the Bolte Bridge, with its two tall concrete pylons. The flat brown river and city buildings are on our left and a mass of factories is on our right. We travel along in silence for a few kilometres, past service stations and spare parts manufacturers, drive-in food joints and masses of nerve-wracking, heavy traffic. Then I see the lift of the West Gate Bridge curving up ahead like a long-forgotten promise about to come true. I wind down the window and let a rush of fresh breeze hit me in the face. Yes. I push down the indicator, pull over to the right and join the stream of cars and big noisy semitrailers and trucks making their way up onto the bridge.

Once up there everything shifts again. You can see all around in every direction. Oil refineries and factories, and huge container ships docked around the port. In the distance, great tracts of housing estates. And beneath us, the river is laid out like an ancient brown limb still flickering with life. Brightly coloured boats are tied up along the edges, like toys. I think of my ex-best friend Zoe. So often it was the both of us up here, looking down across the city on our way to the coast. Her mother, sour and mostly silent, would take us as far as Geelong, chain smoking the whole way, and drop us at the bus stop. We didn’t care about the sourness or the smoking. Zoe and I would be in the back seat with the windows open, humming, grinning, giving each other the thumbs up. Soon we’ll be there, was what we were thinking. Soon we’ll be drinking cocoa and reading trashy magazines, eating grilled cheese on toast, or chips from the shop, and getting our things together for the half-hour walk down to the waves.

I had my first surf on my sixteenth birthday. Zoe and I had just come in from a swim and we were looking longingly out at the surfers skimming in on the waves when this funny little guy came out of the water with his board under his arm. His blond hair hung in his eyes like old seaweed and his long faded shorts had slid halfway down his bum.

‘Hey girls,’ he grinned as he passed us, ‘how you goin’?’

‘How long does it take to learn?’ I remember asking him.

‘Depends,’ he frowned, ‘on how much you want to.’

His name was Charlie and within half an hour he was offering to teach us. By the end of that summer we both had boards.

As we come off the bridge I switch on the radio. I’m desperate for some music but there are just weather reports and traffic updates and the same news headlines that I’d heard at seven o’clock that morning.

‘I need music,’ I mutter.

‘Need?’ Mum asks, amused.

‘Yeah,’ I say gruffly, and begin to flip through the CDs. ‘You don’t mind, do you?’ A certain edge creeps into my voice. You’d better not mind because this is my trip, my van and I don’t even really want you here . . .

‘Of course not.’

I’m still thinking of Zoe so I flip on an ancient Doors album just for the hell of it. ‘Break On Through (to the Other Side)’ comes roaring out of the speakers.

‘Well I certainly don’t mind listening to this!’ Mum coos, throwing her head back, closing her eyes and putting both feet up on the dashboard. ‘This is my music.’

‘No it’s not!’ I snap before I even think. ‘Music is music. It doesn’t belong to any one generation!’ Mum just smiles and says nothing. And I wonder again what has got into me. When exactly did I turn into such an uptight . . . bitch?

Zoe and I were the only girls in our year at school to take

music seriously. Most of the other girls were into the big easy-listening bands or all the doof doof crap. Worse still, Britney and Kylie and the rest of the soft-porn stars. They read the trash magazines and kept up with the frocks and the love lives and the publicity stunts.

But from the time Zoe and I were about fifteen we thought all that was complete shit. We loved the old stuff from the sixties and seventies and, of course, the great current bands who still know what rock is about. There is a heap of good, hard rock around, but you’ve got to know where to look for it. The big stores don’t always keep the stuff we’re interested in.

At about sixteen, we started sneaking into pubs to listen to the new bands around Melbourne. We got hauled up for our IDs, but never got into too much trouble. Coppers would turn a blind eye because they knew we didn’t drink. We were there for the music. We’d often listen to the likes of Black Sabbath, and Pearl Jam, or maybe the Peppers or the Clash, just to get us in the mood before we went to see live bands.

‘God Rose!’ Mum breaks into my thoughts with a sudden laugh. ‘This stuff takes me way back.’

‘Yeah,’ I say sharply, but I don’t comment in case she takes it as a cue to start reminiscing. I’m actually wishing like hell I’d put on something she didn’t understand, something tougher and more complex. She’s right. This is her music. Why the hell am I playing stuff from the sixties?

‘Do you ever hear from Zoe?’ my mother asks. I shrug casually but the question freaks me. I didn’t mention Zoe did I? How come she knows what I’m thinking about? Anyway my mother knows the answer. She knows I don’t see Zoe, so why ask?

‘I miss her,’ Mum says quietly.

Bully for you!

‘Yeah well,’ is all I can manage as I slip up into fifth gear and step on the accelerator. ‘I’d get over that, if I were you.’

Don’tcha just hate someone bringing up something or someone you are trying your best not to think about . . .

The road opens out before us, almost completely flat all the way to Geelong. For miles and miles it feels a bit like we’re skidding across this shiny plate of dreamland. Through the industrial suburbs, factories and giant storehouses, engineering plants and nests of refineries that sit there like pieces from a giant’s toyshop. Those huge steel girders holding up the powerlines, the acres of housing estates, all that industry and people living different lives. It enthralls me in a way. The road cuts through it all like a major artery bringing blood in and out. We are flanked at different points by huge sound barriers and then after a while wide banks of grass and native shrubs and trees.

When at last we are out on the straight open road, the tight ball that’s been sitting inside my chest all morning unravels a fraction. I try to think of some nice thing to say to Mum to make up for biting her head off about music but . . . I can’t. I’m sitting on 100 and the van is purring beneath me like a lazy big cat. It’s weirdly intoxicating to be thundering past the green signs pointing off to other places. Pity the poor bastards going to Werribee or Hoppers Crossing or any of the other shitty boring places! Above me the sky glows deep blue and cloudless in the bright light of morning. There are storms predicted for the late afternoon along the western coast but I don’t believe it for a minute. This is okay. I can think of a lot worse places to be.

‘You want to stop for a quick coffee in Geelong?’ I ask. It’s the nicest thing I can come up with in the circumstances. I don’t want to stop but Mum loves her morning coffee.

‘Okay,’ she says brightly, and unwinds her window and begins to hum a little. Is she trying to tell me she’s enjoying it all so much, that life is a breeze and she hasn’t a care in the world? Naturally I find it irritating. Life hasn’t been a breeze for my mother for some time, so why pretend?

My thoughts are cut short by a fancy BMW pulling out in front of us almost causing me to crash into the back of it. I slam on the brakes.

‘Shit,’ I mutter under my breath and Mum murmurs in agreement and smiles at me in this dry, offhand way that makes me think I might have imagined her previous false note. Maybe she isn’t acting at all. Maybe she really is feeling good. I’ve spent virtually no time with my mother over the last ten months so how would I know?

Sometimes I wonder if I’ve imagined everything. Truly, I do.

Don’tcha just hate it . . . when every thought you have is somehow undermined by an opposing thought? You think you’ve got the situation tied up and then this sneaking little doubt rolls in, making you question the way you see . . . everything?

Ah no. No. That’s not going to work. Too complicated, too introspective. Can’t make a piece out of that. Or can I?

Don’tcha just hate it . . . is the subtitle Roger gave me for the 300-word column I write every week for the music paper Sauce – it’s free and can be picked up in the bar or café nearest to you! Roger’s the owner and editor of the paper, and the twin brother of Danny, who owns the café where I work as a waitress.

I approached Roger about three months ago, when I found out what he did – music being the one thing left in my life I still loved. But he told me there were way too many experienced rock journalists around who couldn’t get work and suggested I try something else. I thought he meant try some other occupation like picking fruit or answering phones, but I didn’t take offence. They’re nice guys both of them: early forties, fat, friendly, nerdy and fast-talking, always out for a quick buck. But I like them all right, because both of them are quick to see the funny side of anything going on, and they’re always nice to me. I appreciate that because I don’t see many people these days.

A couple of weeks after being given the dud news about my chances of writing for his paper, Roger comes around to the café to see his brother. He gives me one of his hearty shoulder squeezes, tells me I’m looking good, and that I’m the best waitress his brother has ever had. Then he asks me for two specials, which means espresso coffee bitter and strong enough to give an ordinary person a heart attack. When I bring them over to where the brothers are sitting near the window in the café, I can see they are engrossed in a serious conversation – unusual because they usually jostle and laugh and slam each other around like guys half their age. So I put the coffee down, prepared to depart quickly. But Roger looks up with one of his wary smiles and motions to the spare chair.

‘Hey Rose,’ he says, ‘have a seat. How’s life?’

‘Okay,’ I shrug, not wanting to sit down because, although the lunch-time crowd has gone, there is still plenty of clearing up to do behind the counter.

‘Just okay?’

‘Just okay,’ I smile back at him. ‘You know how it is.’

‘No, I don’t.’ He is looking at me seriously now. ‘How is it, Rose?’

I stand there smiling stupidly, determined not to give anything away. The fact that nothing much is happening in my life is entirely my own fault. I know that. In a weird way it’s exactly how I want it too. Anyway, boring people with oh-woe-is-me details is not my style.

‘Come on,’ he insists. ‘Sit down, why don’t you?’

I sit down and give one of my hey-guys-I’m-already-bored-with–this-conversation groans, then I cross my arms tight across my chest, throw my head back and look at the ceiling.

‘What’s up?’ Roger asks me.

‘Well,’ I say, watching a fat blowfly make its way slowly across the greasy blistered paint above me, ‘don’tcha just hate it when every day seems more or less like . . . every other day?’ I wait, still looking at the fly but nobody says anything so I eventually sit up again and stare at them. Roger is nodding up and down like an old sage and Danny is lining up the sugar sachets in a straight line across the table – a sure sign he’s thinking hard about something. I find myself suddenly shy, hoping he’s not thinking about me or what I’ve just said because I don’t want sympathy. I don’t want anything to change at all between me and these two guys. I enjoy their daggy humour and all that breezy couldn’t-give-a-shit chatter. It makes me feel like I’m part of t

hings without having to give anything away.

After a bit of a pause Roger looks up.

‘So write a column about it,’ he says to me.

‘About what?’ I say.

‘About the things you hate,’ he replies. ‘It’s exactly what we need, a short dark piece every week from the young female point of view.’

‘The things I hate?’

‘What do you reckon?’

I shrug, trying to get my head around what he might mean.

‘All the things that piss you off,’ he adds, winking broadly at his brother. And suddenly he throws his hands in the air and starts yelling. ‘The price of bloody drinks in bars, Rose! Guys that don’t come through! Ya family.’ He pauses for a moment and looks out the window before turning back to me. ‘George Bush and the friggin’ war. High heels that crack your ankles. The way lipsticks melt! I don’t know, Rose! Girl things. Big things and small things and every bloody thing in between!’

I nod slowly, a bit taken aback.

‘Think you can?’

‘Why me?’

‘I heard that you were smart,’ he said.

‘Well,’ I shrug, pleased. Danny must have told him about my VCE score. ‘It sure sounds a lot easier than writing about the things I love.’

‘That’s the spirit!’ he says, clapping me on the back, and the three of us suddenly crack up laughing. He pulls out his card. ‘Here. Just email it to me in the next couple of days and we’ll take it from there.’

Careful What You Wish For

Careful What You Wish For When You Wish upon a Rat

When You Wish upon a Rat The Convent

The Convent Queen Kat, Carmel and St Jude Get a Life

Queen Kat, Carmel and St Jude Get a Life Rose by Any Other Name

Rose by Any Other Name